"Let eighty people be killed, or side with Nazis against your own country? “What would you have done?”

“Only God knows.”

“God does not have to choose.”

And there you have it. The one line of dialogue worthy of such an esoteric, intellectual name as “The Magus”. But I get ahead of myself.

In 1965, English author John Fowles released his third-published, but first-written book, “The Magus,” originally titled “GodGame”, which is a much more apt title. It was intended, perhaps, to be many things: a critique of British snobbishness, a grand mystery about how much reality you can trust, a painful vivisection of the failings of young men in society and their slow rehabilitation, a meta-story incorporating auto-biographical struggles and desires. Mr. Fowles had worked on the novel for the previous twelve years, and continued working on it until 1977, when he published a final, revised, “as he wanted it to look” version, which I have spent the past six months reading. The general plot of the revised book, without listing the minutiae of twists and turns, is as follows:

* * *

In the late 1950s, a young British man named Nicholas Urfe, well-taught and ambitious but lacking poetic talent, strikes up a romantic partnership with Alison Kelly, a raucously well-intentioned, sexually-liberated Australian woman. The two both feel outcast from their various aspects of society, and their relationship twists from that of being able to share everything with the other person to Nicholas’s abject refusal to care for her in a deeper way and bring her with him to Greece, where he has found work. She leaves him, heartbroken, for a job as an air hostess; he becomes a despondent English teacher at a remote all-boys school on the fictional island of Phraxos. Nicholas does not get along with anyone, becomes even more bitter at the world, decides to kill himself and considers himself unpoetic for not doing so when he tries, and finally stumbles upon “The Waiting Room,” a mysterious secluded section of Phraxos he had been warned off by the previous English teacher.

At Bourani (that section of island’s proper name), he encounters an old and sharp-minded man named Maurice Conchis. Over the summer, the two of them have a subtle battle of wills, at first debating philosophies and discussing Conchis’s experience in the trenches of World War I, then the whole web tangles with the introduction of Lily Montgomery, a woman who looks exactly like Conchis’s dead fiancée. But wait-- it is Lily Montgomery?! But wait again; she’s actually a schizophrenic and Conchis is her doctor on that part of the island-- Look again, fool; she’s really an actress named Julie Holmes pleading to be believed, and Conchis is a genius director who has semi-imprisoned her!

All the while, dear Mr. Urfe dismisses every bit of intrigue as bull, and tries at all costs to get Lily / Julie to break character and get in her pants. Charming fellow.

As it continues, Urfe has the opportunity to meet Alison in Athens, which he does to spite Conchis for keeping him away from Julie for a week. Nicholas and Alison teeter on the verge of being almost compassionate, and finally rekindle their sexual life together, only for Nicholas to say, “Hey, here’s what’s up with Conchis and Julie, who’s nothing like you; she’s cute and intriguing and I want to get to know her better before I sleep with her!”

Alison, rightly, leaves him, and Nicholas gets a letter later from her roommate that she killed herself. Nicholas finds, to his great disgust (yes, this is a real line from the book) that he actually cries over Alison’s death when it happens.

Going back to the island, he and Julie try to fool around more, but are impeded at every turn--either by Conchis’s other help around the island, or by Julie’s timidity to give herself to him. It frustrates our “urbane” “hero” who should be far more interested in the interesting parts of the story, such as an EXTREMELY GRIM story from World War II that Conchis shares and which is partially played out in front of Urfe, incorporating him into the action itself. This story is crucial, and leads in the film to the quote above: Conchis, as Mayor of the occupied Phraxos, has to choose whether to kill three Greek guerillas, or stand up to the Nazi forces and allow himself and eighty of his islanders to be slaughtered. He chooses the latter, and escapes through sheer dumb luck of the bullets not hitting any vital organs.

Julie learns about Alison’s suicide, which Nicholas was hiding; she terminates the whole “meta-theater” of actors around Nicholas. They finally sleep together; Nicholas is captured by Conchis’s men and put on trial--but as the judge, facing a panel of the “actors” who instead call themselves psychiatrists of different reputable institutes. They’ve prepared an excoriating detailed profile of Nicholas Urfe, especially from the help of Dr. Vanessa Maxwell--Julie Holmes / Lily Montgomery. Nicholas’s judgment of them boils down to whether or not he ought to whip the skin off of Dr. Maxwell’s back with a cat-o’-nine-tails, which he initially wants to do but, remembering Conchis’s moment of decision in front of the Nazis, finally refuses. He’s subjected to a reality-check, seeing Dr. Maxwell copulate with her lover, and is released to the world.

Going back to England, Nicholas discovers that Alison is actually still alive! And was working with them since Athens’ botched vacation!!! And he spends every waking minute imagining torturing her!!!!! And discovers the real Lily Montgomery, an old woman who was Conchis’s childhood friend; Lily de Seitas (aka Julie, aka Vanessa, aka--) was her daughter, and Lily Sr. does not give a rat’s hairy ass about “DO YOU KNOW WHAT YOUR DAUGHTER DID ON THAT ISLAND?!” patriarchal crap about “saving virginity” from a man who sleeps around. Bedraggled, utterly worthless and penniless, Nicholas finally meets Alison again in a wide-open park and spends the time berating, belittling, and finally beating her, imagining that Conchis is watching. Well HA! I didn’t learn my lesson from you; I defy what you were teaching me!

And then he realizes that Alison came back because she really did love him after all this time, and that Conchis wasn’t watching at all; the final truth is that nobody’s watching your mistakes, you just have to live your life yourself.

And John Fowles had the gall to include a sanctimonious line of untranslated Latin, which translates roughly to “Let he who has loved once, love again.”

My ass, John.

* * *

I haven’t forgotten that this is supposed to be a review of the film; I can hear Walt reading this and going “J, where’s the stuff about Michael Caine and Anthony Quinn???” I wanted to briefly summarize the book (and I know it’s not a brief summary, but compared to 700 pages and more plots included…) to give you all a sense of what the story is. Because the film, which is 2 hours, does not give you any sense of story.

Released in 1968, “The Magus” is a British film by Guy Green, a prolific director/cinematographer who actually won an Oscar for his camera work in 1946’s adaptation of “Great Expectations”. That talent behind the visual medium shows: the camerawork by Billy Williams was BAFTA nominated and well-deserving of it. The production, which shot on location in Greece, is minimalist perhaps but lush where it counts: nothing is too lavish to be fantastical, and nothing is so bare as to feel in any way amateur. The sets and artwork are superb, showing off the wondrous Greek forests and beaches. The costumes are similarly real, in keeping with those described in the novel, and fascinating without being distracting.

The talent in front of the camera: Sir Michael Caine as Nicholas Urfe, then 35, handsome and British and well-known from many things, including better-written films like “Jaws: The Revenge”. Anthony Quinn stars opposite as Conchis, and is the stand-out performer in the film, bringing a sincerity to Conchis’s well-meaning coldness that is impossible to look away from. Candice Bergen, who is beautiful and so acclaimed for her work that there’s a Wikipedia page listing her awards and nominations, has the thankless job of portraying all of Julie’s shifting faces, making her seem merely like a dramatic and bad actress in the process due to the lack of screen-time able to justify anything in the story. Anna Karina, whose work in the French New Wave made her iconic, is Anne (Alison, now French), whose character is eviscerated to a whimpering, crying shell that desperately loves Nicholas (“I don’t love you. I love the other person you are… inside.” The core, yes that’s definitely pure, you’re not a bastard through and through) and FORGIVES HIM IN THE SUBSEQUENT SCENES after him LITERALLY ABANDONING HER DESPITE TELLING HER SHE CAN COME TO GREECE WITH HIM.

I have some issues with this film.

The pace, first of all, is intensely fast. It has to be, to condense the book; we saw this with the later “Harry Potter” adaptations, we saw this with “Eragon” though we wish we hadn’t, we saw this with “The Saragossa Manuscript”. If you have a book that is so twisted and turning, so long, and in the case of “The Magus” told first-person so that much of the characterization of things and vague explanations are internally-based, it’s incredibly hard to condense into a two-hour film. To their credit, they attempt it, and initially I gave them praise for interweaving Nicholas and Anne’s England romance into the first half through flashbacks, allowing Nicholas to advance the plot on the island as well. As the film goes on, it became increasingly difficult not to remember the book’s many extra scenes, for the simple reason that if I hadn’t read it I genuinely wouldn’t know what the hell was going on.

In the film, Nicholas Urfe goes to the teaching position in Greece, having broken things off carelessly with Anne in England. In Greece, he learns that the previous English teacher killed himself, and in his desk at school had a paper on visits to “The Waiting Room”. Nicholas goes swimming in the ocean while exploring the island’s remoter side; when he dries off, he discovers a book of poems, and finds “The Waiting Room” and Bourani and goes to return the book. There he meets Conchis, and the two quickly develop an unnecessary and unexplained tension, as if Conchis is impatient to start toying with Nicholas rather than act reasonable and think maybe he just IS returning the book. They have one of their MANY discussions sitting around, or looking at the beautiful landscapes behind them, and it continues in the occasional brief anecdote from Conchis’s life until “Lily” is introduced as the woman from 1913. Nicholas, being left alone with her, immediately says, “I can pinch your bottom or I can kiss you,” which goes over about as well as anyone who’s not a misogynistic sludge-pile would expect. Eventually he gets her to break character by saying he feels like he’s “in a loony bin,” causing poor Candice Bergen to have to act immediately hysterical, followed LESS THAN 10 SECONDS LATER by her being 100% calm and saying oh they’re ringing the bell for you go on up. They start to openly mess with Nicholas. He goes to Athens, has sex with Anne, tells her that he’s met cool people on the island which she interprets immediately as another woman before he tells her that, as well; it’s intercut with a flashback of her saying ,“Hey, I’ve slept with a lot of people, but LOVE IS MORE THAN THAT, I LOVE YOU,” and Michael Caine staring at her or at the middle distance; eventually back on Phraxos someone unknown sends the article about her suicide. Half the book and the subplots are slashed away to get to the World War II scenes, first with Nicholas forced into reenacting it, then with Conchis’s explanation of his involvement. That flashback with Anthony Quinn acting his heart out is genuinely the ONE SCENE that had tension, pathos, and any kind of character arc in it. It was glorious. I miss it so much.

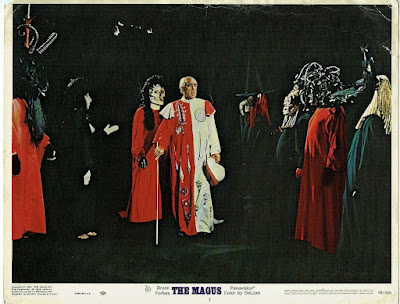

Nicholas almost gets to have sex with Candice Bergen, but he’s jumped and drugged and the Trial--arguably the MOST IMPORTANT SCENE in the book, which offers this irredemably self-centered jackass, after 550 pages, some Goddamn Character Development--plays out with a starry filter, completely lacking a sense of Reality to it or explaining that they’re all psychiatrists trying to show him the error of his ways. It’s beautiful set-design and costuming, as ever. It’s the moment that NEEDS to be emotionally impactful, yet it tries to balance campiness in with its seriousness. Nicholas doesn’t whip Julie’s back despite seeing a film of her with her lover; instead, he loses consciousness and wakes up again in his Athens hotel room. In one twist that genuinely feels like it’s from the mind-games of the book, the hotel room was reconstructed on Phraxos, so that when he opens the door and leaves, he sees Anne--what? Still alive?!--on the Bourani shore below, but cannot get down there before she speeds off in a boat, leaving him alone. Nobody is in Conchis’s house aside from one piece of artwork, which has a cruel, unfocused smile. Nicholas smiles with it and laughs, and we pan over to the water and scream in pain for two hours of our life back.

That’s it, that’s “The Magus”.

To quote Wikipedia’s page on the reception of this film: “The film was a critical disaster. Fowles was extremely disappointed with it, and laid most of the blame on director Guy Green, despite having written the screenplay himself. Michael Caine said that it was one of the worst films he had been involved in along with The Swarm and Ashanti because no one knew what it was all about. Candice Bergen said in an interview about the film: ‘I didn’t know what to do and nobody told me. I couldn’t put together the semblance of a performance.’ When Peter Sellers was asked whether he would make changes in his life if he had the opportunity to do it all over again, he jokingly replied, ‘I would do everything exactly the same except I wouldn’t see The Magus’.” [NB: This quote is also attributed to Woody Allen].

|

| NOT the strangest moment from the film ... |

Besides feeling incredibly bad for Candice Bergen, the main thing that I draw from that paragraph, and from the utterly nonsensical logic of this film's events and lack of character arc, is that JOHN FOWLES WROTE THIS FILM. The studios didn’t screw him over with a rushed adaptation that misunderstood the work: he WROTE THE FILM! And yes, the movie could not include everything from the book, and had a lion’s share of material to adapt in order to draw any kind of storyline; he couldn’t include that Julie had a twin named June who also tried to be alluring to Nicholas, he couldn’t include that Nicholas swears he’s not a racist while being utterly disgusted by the one black character and referring to him in unsavory terms (this omission is fine), he couldn’t include the 200 or so pages at the start and finish that are excruciating to read about Nicholas’s failure to act like a decent human male in England.

Most importantly, he couldn’t include the months--quite literally months--of time it takes the characters to interact and build these complex relationships, and similarly for a reader to go through the events, feeling out each one and evaluating it through the cynical mind of our protagonist. The film does not give us any sense of what time has passed; it could be three days, it could be three years. Everything feels rushed: the characters' interactions spurred by the writer’s necessity to bring their relationships into focus for the next scene, which takes place 50-75 pages later.

OK, THIS is the strangest moment from the film ...

And, to give Fowles credit here, he genuinely did do his best I think to include what pieces of the story were necessary to adapt it in a way that kept it intact in two hours. The story, if you already know it, is able to be pieced together, and might be on repeated viewings of the film alone. The ending, like the book, leaves things ambiguous to instill an esoteric deeper meaning: in the book, it is that we must move on from these mistakes, because nobody is watching and calculating and the world just moves on. In the film, it seems to be that we must smile in the face of cruelty and disaster because sometimes there’s nothing else to do, and that smile will help us carry on.

In an odd way, despite sacrificing any semblance of closure and satisfaction, the endings do feel like, removed from the situation of wanting closure and satisfaction, they have messages that are genuinely helpful. As someone with anxiety, I’ve actually thought about the ending of Fowles’ book and thought, “you know what, it’s just me and the Universe sometimes, and all that matters is how I get back up and keep going.” There’s no grand trial for us, it’s just about how you persevere, and that can happen with a smile, even in the most loveless, bedraggled instances, if we can find the smallest thing to smile about.

The main issue for me in either medium is that Nicholas does not have a character arc; he is bland, and is always meant to be. To summarize Fowles in his introduction to the book, he chose the last name “Urfe” because it sounds like “Earth”; he’s the everyman! And unlike the book, where he spends so much time rejecting society and trying to spin every turn as, “I’M AN OUTCAST, I’M DIFFERENT FROM THEM, I’m more intelligent and smarter and handsomer and better at sex and, and, and I could be a poet and ...”, Nicholas in the film does feel more like a normal guy. He’s not a good person; he’s not meant to be. He’s the man who only cares about sex: he looks like he’s outwardly smart, maybe even charming, and there’s nothing in the world he gives a damn or has compassion about except feeling sorry for himself when women turn him down. Because we’re so out of his head in the film, we aren’t subjected to his inner monologuing; he’s just another gross guy who would hit on women in a pub, be told no, and call her a bitch for it. In modern terms, he’s an incel.

He has no character arc, perhaps to get to the realization of the final pages of the book, or the laughing smile of Michael Caine in the film. He can’t change until the very last minute, because then the punch of the intellectualism of the ending wouldn’t be achieved.

But honestly, if you’ve suffered through 700 pages of this man, or even two hours, you’re not looking for intellectualism. You’re looking for something to hold on to to care about humanity. Because none of the cast of characters gives us any reason to, aside from poor, beaten Alison in the book.

John Fowles wrote other books that are, reportedly, much better. He wrote “The Ebony Tower”, “Daniel Martin”, and most famously, “The French Lieutenant’s Woman”, which was made into a five-Oscar nominated film with Meryl Streep and Jeremy Irons. Fowles detested the film version of “The Magus” and passed away in 2005 at age 79.

In all honesty, I personally started this journey because I knew that “The Magus” was the one book, the one single book, that my father just could not get through in one sitting. It always upset him too much, and he would stop, put it aside, read something else, and eat the pages in chunks like Mithridates VI taking a small ounce of poison a day to build up a tolerance to it. I started “The Magus: Revised Edition” saying “okay, it’s not going to be that bad!”

The first lines, opening the book, on the small page that is supposed to sell you on buying it in the store, is “MORE THAN A NOVEL: AN EXPERIENCE”. Oh boy.

The 1968 film, in many ways, is an admirable production. The music is interesting at times, but spends many scenes steering the tone into absurdist levels of itself rather than keeping it subtle. When Anne and Nicholas frolic in their Athens vacation mid-way through, I genuinely questioned if it was a Hallmark film for a moment. But the bared realism of the production: the Greek setting, the genuine art, the earnest Anthony Quinn, are all enough to give this difficult-to-follow, annoyingly arcless film enough spirit to be memorable. Conchis will wait at Bourani for each of us, perhaps; he will wait to see what makes us tick, and what breaks us down to our human core--the core our loved ones care about us for which we shell up sometimes behind layers and layers of incongruous cruelty.

|

Oh, and if you get a copy of the book, skip to the middle, where there’s a few pages of Nicholas being hypnotized into what seems to be astral projection. It’s genuinely a scene of indescribable awe. Understandably cut for time in the film; way of the world.

“The Magus” is, indeed, an experience.